The Pied Babbler Research Project

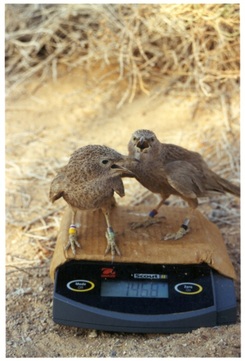

The Pied Babbler Research Project was set up by me in 2003 with the purpose of collecting long-term detailed information on cooperative breeding behaviour. With the help of Nichola Raihani (who went on to do her doctorate on the population), I established a fully habituated population of pied babblers at the Kuruman River Reserve in the southern Kalahari Desert. Now we walk with each group during the day, making observations of their behaviour, sound recordings, and conducting small-scale experiments. Currently, there are 21 fully habituated groups in the population, with group size ranging between 3 and 10 adults. The number of groups in the population each year varies widely - droughts and heatwaves can heavily impact group reproductive success and occasionally result in group extinctions. Each individual in the population is identified through a unique colour-ring combination, and individuals jump onto a top-pan balance to be weighed on a daily basis.

What is a pied babbler?

A pied babbler is a medium-sized (70-95 g) passerine bird. Its distribution is centred on the Kalahari desert, South Africa, where it most commonly inhabits the dry riverbed areas and acacia savannas. It does not occur in the vast grassland areas of the Kalahari and its distribution is therefore very patchy. The pied babbler is a cooperative breeder - it lives in groups that cooperatively defend a territory year-round. Each group has one dominant male and female that have almost exclusive access to all breeding activity. Subordinate adults help to raise the young produced by the dominant pair. All group members contribute to raising young (including provisioning them with food, incubating the nest and sheltering young from inclement weather), sentinel duty, territory defense, and predator mobbing. Group members interact regularly and are rarely more than 20 m apart throughout the day. Not only do they forage together, group members also regularly preen one another, playfight, huddle and roost together. Babblers are highly vocal, and these calls provide them with information about the presence of predators, neighbouring groups, hungry young, or birds that are in distress.

Babbler society is highly dynamic - within our population we have evidence of eviction, divorce, infanticide and kidnapping. Our long-term research suggests that these dramatic events are related to the continual struggle between group members for dominance and access to breeding opportunities. These struggles can sometimes result in a dominance overthrow or successful cuckoldry, but these events are relatively rare.

Our long-term database, where we can track the life history from an individual from when they hatched to when they died, reveals that pied babblers can live for up to 15 years in the willd.

Babbler society is highly dynamic - within our population we have evidence of eviction, divorce, infanticide and kidnapping. Our long-term research suggests that these dramatic events are related to the continual struggle between group members for dominance and access to breeding opportunities. These struggles can sometimes result in a dominance overthrow or successful cuckoldry, but these events are relatively rare.

Our long-term database, where we can track the life history from an individual from when they hatched to when they died, reveals that pied babblers can live for up to 15 years in the willd.

The Arabian Babbler Research Project

The Arabian Babbler Research Project was set up by Professor Amotz Zahavi in 1974. Professor Amotz Zahavi and his wife, Professor Avishag Zahavi, have been monitoring the population ever since. The research site is located in the Shezaf Nature Reserve, in the Negev desert, southern Israel. Unlike the Kalahari desert, the Negev desert is a true desert - it is extremely arid, with an average annual rainfall of less than 50 mm per year (compared to an average of 260-290 mm in the Kalahari). The Arabian Babbler project has one of the longest running databases on cooperatively breeding birds in the world. On average, there are 25-30 fully ringed and habituated groups monitored each year. Group size typically ranges between 3 and 12 adults, with average group size between four and six adults. Similar to the pied babblers, Arabian babblers are severely affected by drought. In addition, the development of greenhouse farming in the Rift Valley represents a serious threat to the population. There have been many researchers working on Arabian babblers over the many years since establishment - this site refers principally to the research conducted by myself, my colleagues and students.

What is an Arabian babbler?

Behaviourally and morphologically, pied and Arabian babblers are quite similar, and both are from the genus Turdoides. Arabian babblers are slightly smaller (60- 80 g) and are easily sexed by the different iris colours between males and females (pied babblers cannot be sexed in this way). Perhaps due to their drier habitat, Arabian babblers do not move as frequently between groups. Adults may remain in the group as helpers for up to five years. Unlike pied babblers, Arabian babbler adults allofeed each other, and this appears to be a dominance assertion: dominant birds allofeed those that are subordinate to them. However, in terms of group dynamics and social behaviour, the similarities are very strong: all group members contribute to raising young, territory defense, sentinel duty and predator mobbing. In addition, usually there is only one dominant pair within each social group, who monopolize access to breeding activity. Eviction, divorce, kidnapping and infanticide occur in Arabian babbler society, but at a lower frequency than in pied babblers. Both Arabian and pied babblers are terrestrial foragers and spend most of their foraging time on the ground.

The Western Magpie Research Project

The magpies of WA were originally observed by Professors Eleanor Russell and Ian Rowley. In 1995 they established a ringed, habituated population in a small town near Perth (which is now an outlying suburb of the ever-expanding city). Eleanor and Ian observed and monitored between 8-10 groups annually but considered the magpies as their hobby rather than an intensive research project because they were both reaching retirement age. However, they did an impressive job of monitoring and recording movements and recruits to the population over a ten-year period. For several years there was no active research on the magpies. However, after meeting with Eleanor and being introduced to the magpies, I (Mandy) re-instigated research and expanded the ringed population. Starting with Eleanor's six groups, I (Along with my students and collaborators), have expanded the population to 17 groups of magpies (group size ranging between 3 and 14 birds) in two locations in the Perth urban matrix. Research was initiated on the population in 2013, and observation and habituation occurs in a similar way to that described for the Pied Babbler and Arabian Babbler Research Projects. Group size and the number of groups varies annually.

What is a Western Magpie?

The Western Magpie (Cracticus tibicen dorsalis) is a subspecies of the Australian magpie inhabiting southwestern Australia. Magpies vary in their level of sociality over the Australian continent, with cooperative breeding relatively rare on the east coast, but far more common in the west. The Western Magpie is a large (260-350 g) passerine bird that lives primarily in large groups, containing between 3-16 adults. It most commonly inhabits open grassland areas, but has adapted well to human modified landscapes and is commonly seen in urban parklands and reserves. The Western Magpie is cooperative, but not in the traditional sense of cooperation epitomised by the Pied and Arabian babblers. Instead of a single dominant pair, all females in the group may attempt to breed. Often, those that fail to breed become helpers at the nests of other group members, but this is not always the case. In some cases, birds will be present in the group as neither helpers nor breeders. Group members also cooperate in predator defence and food excavation. One of our goals is to determine exactly how cooperative this species is, and what factors promote the occurrence of varying levels of cooperation. Previous research on the population by Jane Hughes and colleagues has revealed extremely high levels of extra-group paternity (>80%), suggesting that group-living in the magpie is somewhat different from the traditional high skew cooperative breeding systems typified by Arabian and pied babblers. Magpies have extremely complex and varied vocalizations, and are considered 'one of Australia's most highly regarded songbirds'. As of 2020, there are still magpies alive that were ringed as adults in the late 90's, indicating a very long lifespan for this species.